LIVING HERITAGE, LIVING CLASSROOM | Fostering Intercultural Understanding at a Malaysian Wet Market

UNESCO APCEIU | Issue 64 SangSaeng | Best Practices

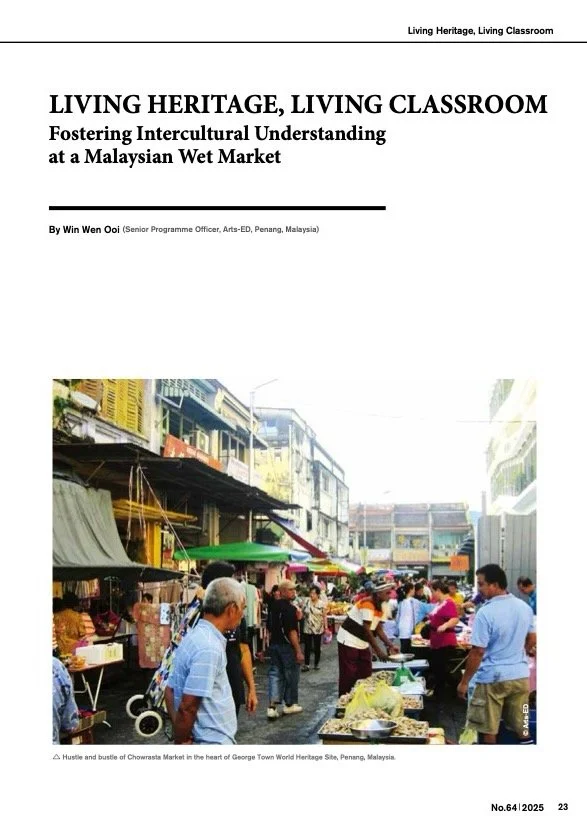

Step into a typical wet market in George Town, Penang, and your senses are immediately immersed. A cacophony of languages and dialects—Hokkien, Malay, Tamil, English, and Mandarin-fills the air, weaving through the distinct aromas rising from every corner. There is the sharp tang of the sea from glistening piles of fish and prawns, much of which arrived fresh that morning from Thailand or Gertak Sanggul, on the coast of Penang Island. Then there is the earthy scent of freshly harvested vegetables- some perhaps from nearby farms on Penang Hill, the cooler Cameron Highlands, four hours’ drive away, or various regions of China. The market pulses with the rhythm of daily life. Watch as the third-generation mutton vendor meticulously wipes his knife before carefully setting it down, a small ritual of respect for his trade. Listen to the steadfast, percussive chop-chop-chop as a fishmonger expertly portions a large fish for a restaurant order. Another vendor deftly skins and debones chicken thighs, following precise instructions from an elderly aunty planning her favourite home-cooked meal. A young customer earnestly consults a vendor on the most suitable blend of chilli paste for his father’s squid curry. Amidst the bustle, several students, clipboards in hand, are navigating the stalls with a focused curiosity that distinguishes them from the regular shoppers. “Excuse me, Uncle,” one student asks a seafood vendor, pencil poised. “Where do these prawns come from?” The vendor, pausing his weighing, explains the difference: “These ones from the farm, cheaper lah. These ones from the sea, fresh but cost more.” The other student chimes in, “Why do we need to farm prawns?” Meanwhile, a pair of students are sampling prawn dishes in a “kopitiam” (coffee shop) right next to the market. The hawker explains, “We only use fresh sea prawns! Hokkien Mee must have the best fresh ingredients. Not like some places now using frozen, pre-packed.” These cross-generation and often cross-cultural interactions are at the core of Community-based Learning programmes organised by Arts-ED, a Penang-based non-profit organisation. Prompted by intentionally designed activities and tasks, these exchanges encourage young participants to cast a more critical eye at what we often take for granted: where does the food on our plate come from? Why do we eat what we eat?

Penang’s Food DNA – Unpacking Culture Through Turmeric

The wet market is deeply intertwined with the city’s history as a bustling port city, a pivotal hub in the centuries-old spice trade, owing to its strategic location in the Straits of Malacca. The constant movement of goods and people-traders passing through, migrants settling down-transformed George Town into a dynamic melting pot. This convergence of cultures shaped not only its architecture but also the intangible cultural practices embedded in daily life, particularly its foodways, which have helped earn George Town its UNESCO World Heritage Site status. Some of our programmes at Arts-ED focus on the relationship between history, migration, and cuisine. For example, one programme uses a ubiquitous spice, turmeric, as an entry point for young learners to investigate the multicultural identity of the place. Participants embark on a treasure hunt in the market, seeking out turmeric in its various forms, from the knobbly fresh root to dried slices and vibrant yellow powder. They observe its presence in dishes unique to different cultural groups within or near the market. Crucially, they interview vegetable vendors, sundry shop owners, cooks in nearby eateries, and even customers to understand the journey of turmeric from stall to table. For many participants, the greatest surprise comes in discovering the diverse uses of turmeric across different communities. While its yellow hue and slightly earthy flavour are familiar in dishes such as fried chicken and curry, they delight in learning-through interviews and onsite observations-how turmeric features in Hindu rituals, is used to dye fabrics, and plays a role in traditional Indian medicine for treating ailments such as inflammation, digestive issues, and skin conditions. Participants then compare the functions and meanings of turmeric across Malay, Indian, Chinese, Peranakan, and other cultural traditions, noting how knowledge has been passed down through generations, echoing historical trade routes and cultural exchanges. Connecting back to the personal, students reflect: “What role does turmeric play in my own family’s traditions? How have our practices related to spices in general been shaped by life in this multicultural city?” This process transforms a simple market ingredient into a powerful tool for understanding historical legacies, appreciating living heritage, and connecting personal identity to the broader story of Penang.

People-to-People Connection – Learning from the Keepers of Living Heritage

Beyond the ingredients and historical narratives, it is the people who form the beating heart of the wet market. The vendors, many from families who have worked there for generations, are living repositories of heritage, embodying skills, knowledge, and cultural practices passed down through daily economic and social routines. Recognising this, another programme shifts the focus from product to person, fostering deep connections between young learners and the market community. This programme begins with introspection, encouraging students to reflect on their own identities, backgrounds, hobbies, and future aspirations. They then step into the role of apprentices, working in small groups assigned to specific vendors. For several days, they immerse themselves in the vendor’s world, experiencing the rhythm of the workday-from setting up stalls at the crack of dawn, through the busy hours of preparation and selling, to packing up at day’s end. A group of students, apprenticing at a tea stall just outside the market, observe and document the vendor uncle’s process of making the famous ginger tea; how he interacts with customers and socialises with nearby vendors and workers. During quieter moments, the students interviewed the uncle about his life and work. They even attempt to learn how to pull the frothy “teh tarik” (pulled tea), laughing together as they realise just how much skill and practice it takes to craft this everyday drink. As one participant shared, “My group can now better appreciate other people’s jobs, even if it looks easy!” These interactions foster relationships that transcend conventional classroom learning. Through shadowing, observing, and participating, students develop a profound understanding of vendors as individuals, gaining respect and appreciation for their professions and aspirations. Students cultivate empathy and learn to engage with lives and perspectives vastly different from their own. Read more.

Read the full issue: https://www.unescoapceiu.org/post/5396

Special thanks to APCEIU for inviting us to contribute to the Best Practices section of the 64th issue of SangSaeng.